by Jon Allsop

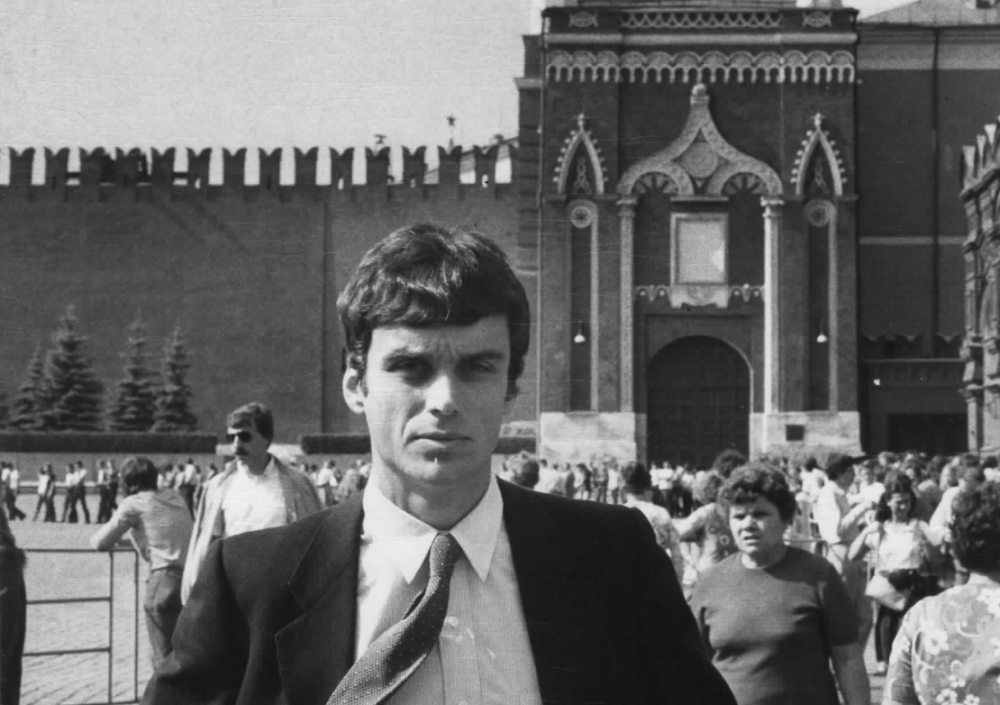

In the early nineteen eighties, Andrew Nagorski, then Moscow bureau chief for Newsweek, traveled to report from Vologda, a city in a famed dairy region that was struggling with local supply. Nagorski had to register his trip with the authorities, who would usually get someone to “glom onto you, as kind-of your minder.” In Vologda, the deputy editor of a local newspaper showed up to greet Nagorski at the train station and offered to show him around. “I thanked him very much and basically blew him off,” Nagorski recalls. The editor gave Nagorski his card.

Later, a local police officer stopped Nagorski and asked him what he was doing. “I was being followed by the KGB, but this uniformed cop seemed not to be in on the story,” Nagorski says. “He was genuinely, I think, puzzled: How could an American be there?” (In those days, US foreign correspondents were not a common sight in provincial towns.) Nagorski pulled out the editor’s card and handed it to the cop. “I said, Look, if you have any questions about who I am, here’s the card from your local newspaper. Ask this guy.”

In August of 1982, Nagorski was called into the press department of the foreign ministry and told that this exchange constituted impersonation of a Russian journalist. Nagorski, whose parents came from Poland, speaks Russian but his language skills were “so-so,” he says, and there was no way he could pass for a Russian. In addition to that impersonation accusation, Nagorski was accused of posing as a Polish tourist because he had spoken Polish on a reporting assignment, and of violating traffic regulations on a trip to Tajikistan, where he’d gone to ask young Soviet Muslims about the Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan, which had started in 1979. Collectively, these infractions amounted to “impermissible methods of journalistic activities,” Nagorski was told. He was expelled.

Nagorski was not the first American journalist to have been kicked out of the Soviet Union after his reporting riled the authorities during the Cold War, and he was well aware that reporting in the bloc could be a minefield. He was wary of attempts to entrap him; in one case, he was on the street in Moscow when someone started walking alongside offering him photos from inside sensitive military zones. “That just smelled to high heaven,” Nagorski recalls. He walked away, but striking a balance with wanting to follow legitimate tips could otherwise be difficult. “If you’re there, you gotta report,” he says. “Otherwise, why go?”

Still, Nagorski didn’t particularly fear that he would face a worse penalty than expulsion, such as charges for espionage. Expulsion, of course, was no small matter—covering the USSR was “the most important journalistic assignment possible in the Cold War,” Nagorski says—but he didn’t feel physically at risk. “You knew it was possible but you thought it was probably unlikely,” he says. Russians who spoke out against the system “were the ones who were risking prison, even psychiatric hospitals, and in some cases their lives. By comparison, Western correspondents [had] a very tense reporting assignment, but you didn’t feel the same level of risk.”

Ultimately, “expelling me was more than just a story of retaliation against one journalist,” Nagorski says. “It was an indication of their mood, of bad relations between the US and Moscow.” After Nagorski was expelled, the US State Department kicked out a senior correspondent for Izvestia, the Soviet propaganda paper, in response.

In 1986, an American journalist was accused of espionage in the Soviet Union. Nicholas Daniloff, the Moscow bureau chief for US News & World Report, was already planning to leave the bloc when he met in a wooded Moscow lane with a friend of four years. He handed the friend some Stephen King books in exchange for what he thought were newspaper clippings. They were actually photos and maps, one apparently of Afghanistan, stamped with a “secret” designation. In Daniloff’s case, too, geopolitics were involved; the US had recently detained a staffer in the Soviet mission to the United Nations, also on espionage charges. Daniloff and the Soviet detainee were soon swapped, but not before Daniloff had spent thirteen harrowing days at Lefortovo prison in Moscow. “I was a pawn in a superpower game of strategy and will,” he wrote following his release.

A few months later, Ann Cooper arrived in Moscow to serve as a correspondent for NPR. Daniloff’s case had attracted a great deal of international attention. Yet Cooper “didn’t sense a big chill in the foreign correspondents who had been there during that period,” she told me. A sense of being under surveillance remained constant—foreign correspondents in Moscow lived in special buildings and assumed the phone lines were all bugged, Cooper recalls—and yet in general, the atmosphere for free expression in the bloc appeared to be liberalizing. “In the time that I was there, everybody felt freer, not just the foreign correspondents,” Cooper says. “We were careful to try to do everything we could so that our sources would not run into trouble or suffer any consequences. But I don’t think most of us in the foreign correspondent corps worried about consequences or anything very dire for ourselves.”

Cooper was in Moscow during the period of glasnost, or greater openness in public affairs, initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev; by 1991, Cooper told me in 2021, on the thirtieth anniversary of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the press was “incredibly free, and doing good journalism.” Media freedom would continue to flower through the nineties, including for foreign correspondents. But there were dark clouds ahead. In 2004, Paul Klebnikov, the editor of the Russian edition of Forbes, was shot dead as he left work. At the time, Nagorski was overseeing foreign-language editions of Newsweek and would come and go from a newsroom that his publication shared with Forbes in Moscow. Unlike during the Cold War, it wasn’t clear, in the Russian political environment of the early 2000s, whether the hit had been ordered centrally or by an oligarch, a gang, or some other actor. (Klebnikov’s murder has still not been formally solved, but he covered crime, business, and politics.)

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Klebnikov’s was the eleventh “contract-style” killing in Russia since 2000, when the leadership of the country changed hands. Since then, things have only got worse for the Russian press. I asked Cooper how she’d summarize what changed since the flowering of her stint in Moscow. She replied with two words: “Vladimir Putin.”

In 2017, Evan Gershkovich, an American journalist who is the son of two Soviet émigrés, arrived in Russia. He worked first for the Moscow Times, then for Agence France-Presse, at a time when the domestic press was being targeted with increasingly draconian official restrictions. Independent news organizations and their staff were tagged with the label “foreign agent,” which was humiliating and came with burdensome bureaucratic consequences. And numerous reporters were jailed. In 2020, Ivan Safronov, a former defense journalist who had recently quit his job to work as an adviser to Russia’s space agency, was arrested on treason charges related to his media work. Last year, he was sentenced to twenty-two years in prison.

Through all this, as Joshua Yaffa, a New Yorker journalist who knows Gershkovich, wrote recently, foreign correspondents “continued to occupy a position of relative privilege and safety”; Putin lacked the power to shut down foreign news organizations, and didn’t see their reporting as an imminent threat to his domestic position. But the war in Ukraine would change that: Putin forced through draconian new restrictions on freedom of expression, and although the effect on foreign reporters was not immediately clear, many American journalists left Moscow, including Gershkovich, who had only just landed a new job at the Wall Street Journal. Gershkovich would soon return, hoping, Yaffa writes, that “the old logic might still apply” to foreign reporters. In the months that followed, he covered many important stories about the war, even as vises closed around him. Last July, he tweeted that “reporting on Russia is now also a regular practice of watching people you know get locked away for years.”

Last week, Gershkovich himself was detained, and charged with espionage, during a reporting trip to Yekaterinburg. He was arrested in a local steakhouse, then transferred to Lefortovo prison. The Journal vehemently rejected and condemned the charges against Gershkovich, as did the Biden administration. Daniloff, who is now eighty-eight, told US News & World Report that he felt as if history was repeating itself. “That is a rather sad, sorry, state of affairs,” he said.

Like with Daniloff, the Putin regime may have arrested Gershkovich with a prisoner swap in mind. But this is far from certain; either way, it seems, based on the noises currently emanating from Moscow, that he will be detained for far longer than Daniloff’s thirteen days. Cooper told me that the apt comparison for Gershkovich’s case may not be that of Daniloff and other Cold War-era correspondents, but the arrest and lengthy detention, from 2014 to 2016, of Jason Rezaian, a Washington Post correspondent in Iran. In a column over the weekend, Rezaian criticized US media coverage of Gershkovich’s arrest for parroting the espionage charges in headlines. Gershkovich, Rezaian wrote, “is a hostage until proven otherwise.”

Cooper sees the Gershkovich arrest as scarier than that of Daniloff. In the Cold War, such events would often follow a sort of pattern, she said, whereas “one of the characteristics of Russia under Vladimir Putin is the unpredictability in situations like this.” Nagorski told me that he would be more hesitant covering Moscow today. “Now,” he said, “I think all bets are off.”